OWN CORRESPONDENT

What can you tell us about yourself?

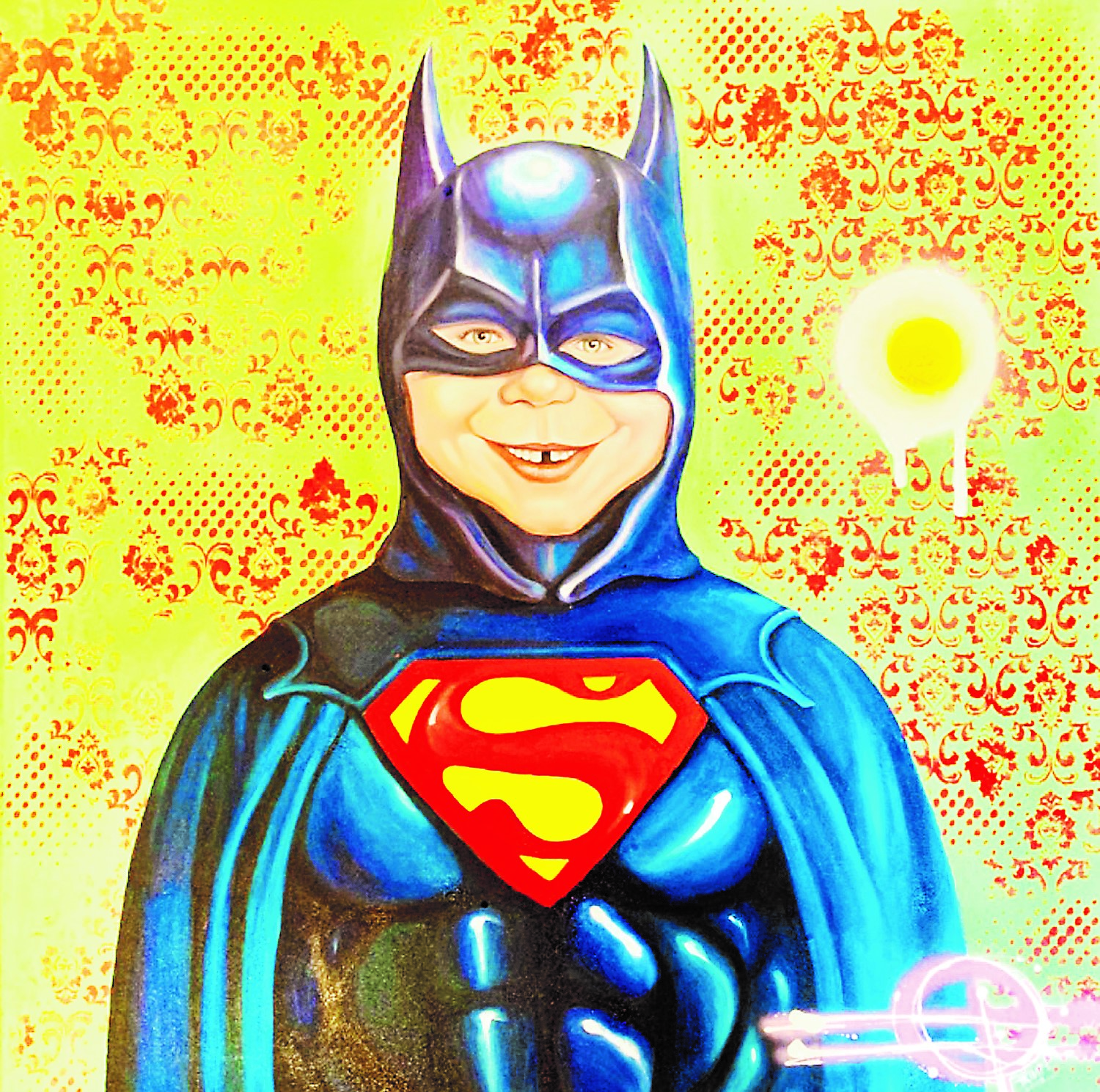

I’m an artist, I’m a businessman, and a family man, I’m a Jew, and I’m my own best-kept secret. Okay, maybe not in that order, but something like that. I have always drawn in notepads – doodled actually – which makes me painful to be with. At some stage, I began to take my sketches, which are quite good if I may say so myself, and imagine them in a bigger format against pop backgrounds. That got me on a trajectory where I started to look at what classic pop art had given to the art world. It’s fun art that plays with well-known brands and famous people. Then I looked at how so many contemporary artists were incorporating old paper, like newspaper magazines and old books, into their artworks and bingo, I found a style. It’s pretty random, but then, so is life.

How easy is it to live with this secret?

It’s a complete mess sometimes. I have to work in a secret space, and wash my hands often, and change my paint-stained clothes all the time. But artists are doing it all over the world now: Alec Monopoly, Banksy, Mr Brainwash, and others. Some of these are my heroes, so I figured if they could be successful at it, then so could I.

When you see your artwork hanging in someone’s home, how do you feel?

I don’t really get to go to people’s houses to see the works. But I see photographs, and I’m always amazed at how versatile they are. I’m into visual contradictions, banging different elements into one another, so I see that the works can function in a minimalist white space as well as they work with people’s collections of precious old things.

When people talk about Fringe, what goes through your mind?

There’s always a moment where I hold my breath, and wait for them to criticise me. Sometimes there’s too much for people to deal with, the anonymity and the fact that the artworks don’t take on South African life headfirst. But more and more people are beginning to understand that we live in a global world, and popular culture is sort of common ground.

What do your closest friends (who don’t know that you are Fringe) think of your work?

Some of them don’t even know it exists. Some of them have been to the Daville Baillie Gallery with me, ostensibly just to look at art. Everyone seems to like the boldness, the colour, and the famous comic-book characters. When they comment, I sometimes get good tips about what I should be trying out.

Why did you adopt a pseudonym? Why don’t you want people to know who you are?

It’s simple, I can’t spend my time dealing with the art scene. I want to make the art piece, and move on to the next. I don’t want to explain myself endlessly, and I don’t want to parade around as the artist in the room. My family wouldn’t deal with it as it is.

How many times have you almost slipped into divulging who you really are? What happened in those instances?

Never, because I just don’t want to deal with it.

What drew you to art?

Every second of every day draws me to art. I can’t look at anything without beginning to ask myself how it would fit in a frame, or how it would look on a plinth. Then, there’s the pleasure principle, in which I want to share my vision with the world.

Do people see you as an obviously arty and rebellious person. If not, how do they see you?

They might see me as arty because I’m always tinkering with things, but they definitely don’t see me as eccentric or rebellious.

How would you describe your art?

It’s classic pop art, with a 21st century edge.

How has your art matured over the years?

I started out producing sketches mixed with collage. Now I regard myself as a copyist and a chameleon. I don’t want you to know where reality ends and art begins.

What inspires you?

My teenage years, my children’s lives with the endless need for the new realities being sold to them on social media, the pop-art movement, and the up-and-down world of art collecting.

What impact does being Jewish have on your art and life?

My grandparents collected art. It was a kind of stereotypical attribute in the earlier part of the 20th century – comfortable Jewish families with well-loved art pieces by amazing artists that hung on the walls. They had a Tretchikoff and a Pierneef. I grew up taking it for granted that the Jewish home was a place of art. I didn’t even pay attention when my parents became collectors because I just saw the pictures, and not their pastime as art lovers. I’m aware that the Jewish community has given us some of the most committed art collectors in the country and the world. I can’t separate myself from the community from which I come, and I think we are very lucky that we Jews support the arts, which makes my job infinitely easier.

What does this particular exhibition mean to you?

The new exhibition is called “No Seriously”, and it’s my most challenging to date. It’s full of visual contradictions, heavy works with light-hearted themes that hopefully will make you reflect on how the process of ageing is so alienating. The frivolity of our youth comes back to bite us as we grow older. I want it to be serious artistically, but it must also give the child in us a great big hug.

What do you think about being compared to Banksy? Other than the hidden identity, do you related to his work at all? If so, how?

Banksy is a master of understatement. I hope that one day I can use plain and simple symbols and characters to such great effect. Right now though, I seem to be heading in another direction. Come and see the exhibition to find out what that is.

Read full article here